Can you imagine a secondhand fashion future?

Mapping fashion businesses on my local high street last year revealed a thriving secondhand ecosystem and almost no shops selling new clothes - is a secondhand fashion future closer than we think?

Imagining fashion’s future

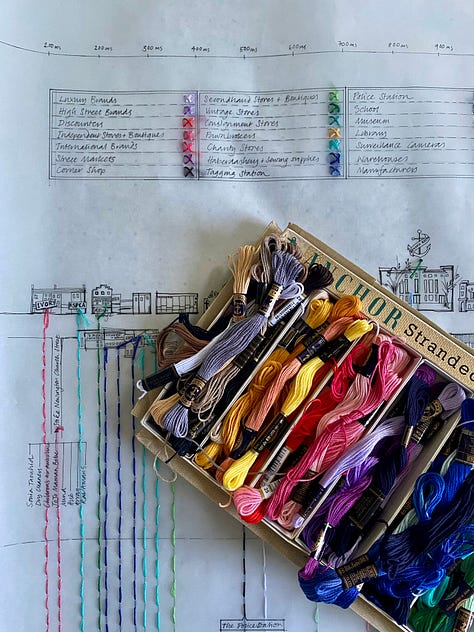

I’ve been researching the secondhand market for almost two years now; and I started imagining and mapping how these secondhand fashion futures might really work a year ago, as part of an MA project that asked us to design and illustrate speculative futures for the fashion industry that could be exhibited in a final show in the Design Museum.

For this project I chose a deliberately dystopian viewpoint. In my speculative future the fashion industry just keeps on growing, and people just keep on buying more and more new clothes. So, by 2040, in the face of catastrophic climate change, governments around the world start banning the production and purchase of new clothes.

Oddly it wasn’t such a difficult scenario to imagine.

Mapping my secondhand fashion future

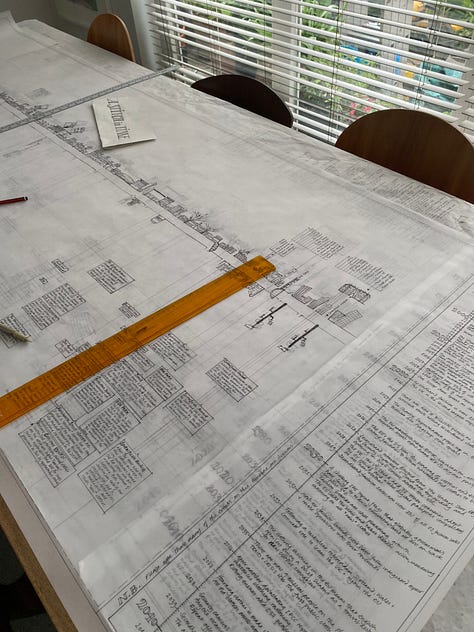

What proved harder was imagining the infrastructure and systems that would supply people with clothes to wear in this version of a secondhand future. So, to help me think through the details of my narrative, I walked the length of my local high street drawing, photographing and documenting all the businesses connected with the fashion industry and operating there today.

I already knew that I’d find lots of secondhand shops and charity stores, but it was a surprise to realise that there were almost no shops selling new clothes.

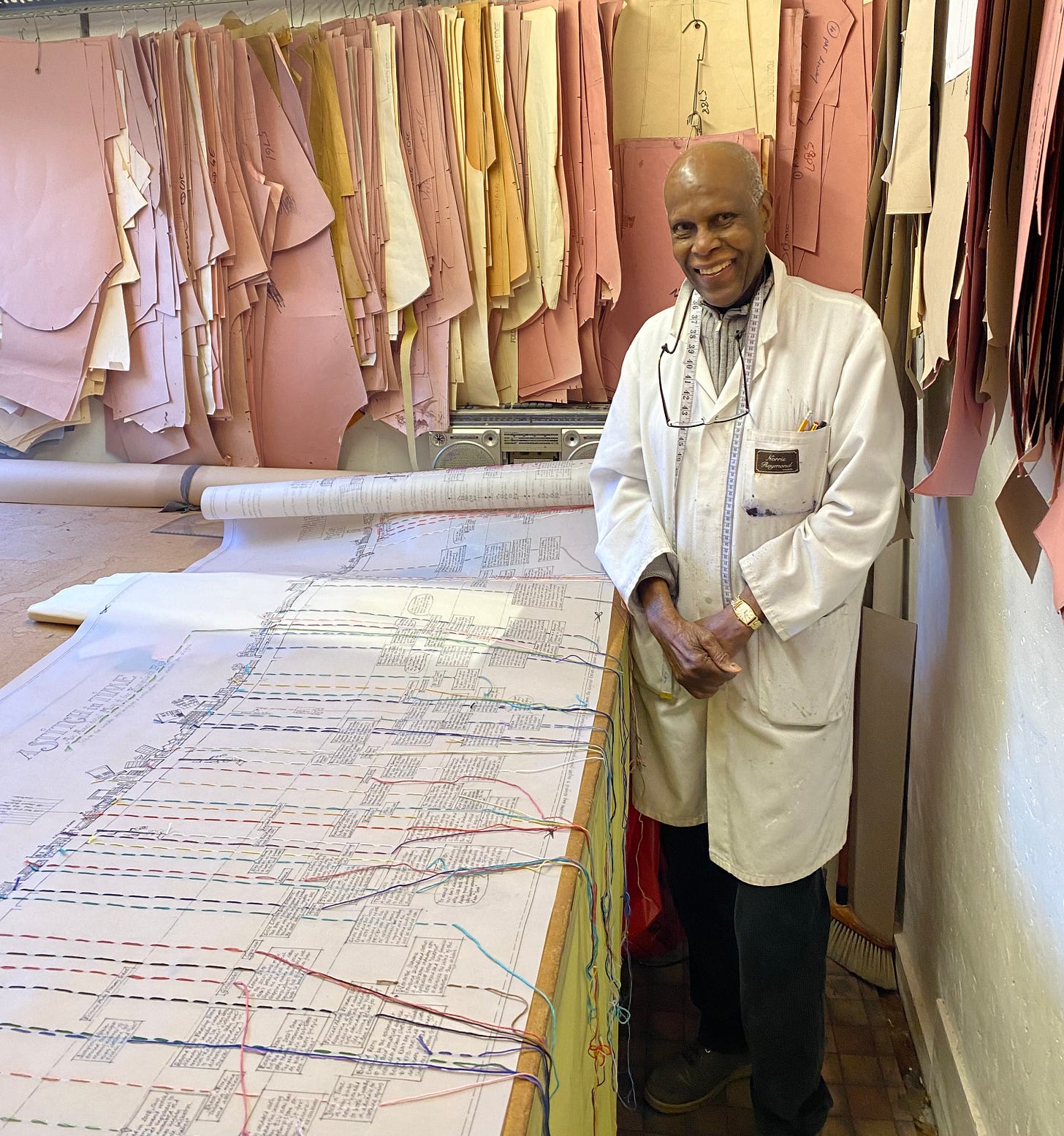

And it was even more of a surprise to uncover a rich history of apparel manufacturing moments from where I live, and to meet craftsmen, like Norris Raymond, who is still producing clothes in Hackney.

Big changes can and do happen

Meeting Norris reminded me that, when I left fashion college in the 1980’s, the textile industry was one of the biggest employers in the UK. Back then, the idea that almost all the new clothes we bought would be manufactured in other countries would have seemed inconceivable. Ironically, now the idea of people making clothes in the UK feels foreign.

Somehow, knowing this made the idea of a future where new clothes are banned seem more plausible.

Stitching together the past, present and future

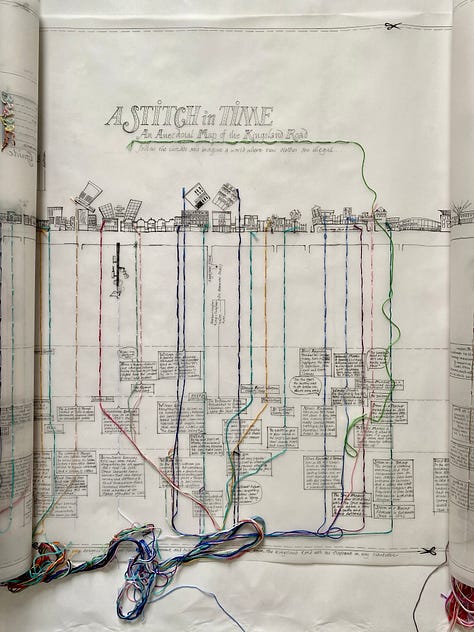

The finished artwork was hand-drawn on pattern paper bought from William Gee, founded in 1906 and another piece of Hackney’s manufacturing heritage, and hand embroidered using a collection of vintage threads that once belonged to my great aunt.

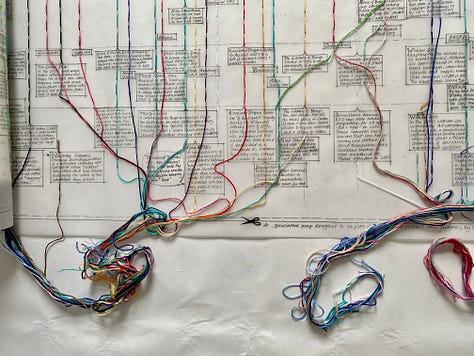

The map is designed to start conversations. It invites the viewer to take a walk with me along the Kingsland Road in Hackney, following the individual threads and exploring its manufacturing past, its charity shop filled present, and its speculative secondhand future.

For this project, I had great fun imagining a future where new clothes were traded illegally on street corners, where shoe repair shops were mobbed, where new industries were created deconstructing old clothes for spare parts and where street security cameras checked the digital product passports in our clothes to make sure we were all wearing nothing new.

But can fashion’s future really be secondhand?

When I chose this title for the panel discussion I’m hosting as part of the London College of Fashion MA Graduation Show I was being provocative.

I don’t think that we’ll only be wearing secondhand clothes in the future but I do think we need to start a meaningful debate about how we can harness the exponential growth in secondhand apparel sales as a lever to reduce fashion’s overall carbon emissions.

That’s the elephant in the wardrobe that I think we should all be talking about.

If you’ve got thoughts on how that could work or want to find out more, the talk is on the 6th of March at 6pm, tickets are free and the link is here.

The intention of this Substack is to start conversations and support my research into whether the secondhand market can be a lever to reduce fashion’s carbon emissions; please tell me what you think and suggest topics I should investigate.

Hi again Gemma,

What a fascinating project. I'm just looking at the images of your art work, and the first thing that came to me was how it reminded me of the map of London underground. That colourful criss-crossing of networks, which I think is a good metaphor for the fashion industry today.

It is also really heartening to hear of people like Norris still in business. I don't know if you're aware of the Garmentology podcast, but there is some very interesting guests talking about both secondhand materials and the return of garment manufacturing in the UK. They're usually quite long deep dives, but rich in information and often great narratives. I've added a link should you be interested, I have no affiliation with the podcast. https://welldresseddad.com/category/garmology/podcast/

Where your research is covering the larger, commercial side of clothing production, my own research is at the micro level, individuals making their own clothes, and what sustainability means to them. Your secondhand fashion future vision has really started me thinking about what a fashion future for home sewists using secondhand materials would look like. It's not something I have considered before so thank you for sparking this idea. I don't think your vision is necessarily that dystopian. If I were to follow your vision, I would expect a future where only the very rich would have access to new clothes, and the rest would have to use secondhand. A reversion to the sumptuary laws of the past. There are already the early signs of businesses deconstructing garments for reuse, and a recent show at Huddersfield University (where I'm based), was around garments that could be taken apart and reconstructed in different ways to promote longevity. So fashion education is already starting to address this. I suspect LCF are doing similar work.

I would love to hear the talk, but am unable to come to London that day. Is there any chance it is being recorded, and if so would I be able to access that recording somewhere?

Thanks again Gemma for sparking some great ideas, and best wishes for your panel discussion.

Claire